Saturday, January 3, 2009

Afterword: U.S. +10

Saturday, December 27, 2008

Patagonia

Rumor has it Magellan named Patagonia for the relatively tall natives inhabiting the land, after the giant Patagons of myths and stories. Even if the original occupants of the region have been killed off by Europeans and sundry, the geography of the place is enough to inspire the awe one might have in the presence of a colossus.

That is to say, the mountains are huge and scary.

Honestly, it's the holidays, school is over, and I think I've just about had it with all the rhapsodical rhetoric. I'll probably want to get mushy wrapping this whole experience up later, so I'm going to keep it pretty bare-bones here.

Guy, Jon, Murph and I flew to Punta Arenas on the Straits of Magellan. We met up with Gina and her brother Matt and took a bus north to Puerto Natales. There were lots of sheep. From Puerto Natales we took a day-long car tour into Parque Nacional Torres del Paine, the main tourist attraction of Patagonia, where hiking trails encircle a series of jagged peaks and glaciers. We came back to our hostel and shared an asado set up by the owners, a pair of rambunctious brothers who then stayed up all night with Guy and Murph. The next day, Gina, Matt, Murph and I went fishing. Murph caught a trout and fried it for lunch. We rented camping equipment. The next day we took a bus back into the park and began a three-day hike.

By the time the hike was finished, I was almost out of money. I spent the next four days laying low in Punta Arenas, walking around town taking in the sights and museums. I met an Australian, an Englishwoman and a Swiss fellow and we shared a hostel and had dinner together.

I flew home to Santiago, bought some last-minute gifts, met up with Guy, Jon and Murph at Basic Bar for a few farewell beers, then went back to Ñuñoa and stayed up all night with my host family drinking more beer and frying empanadas.

I went to bed at two and woke up at four to catch my cab to the airport. My final goodbyes to the Arevalos were a night of greasy fried food and tipsy cheerfulness, which I think is the best possible way to do it.

After 36 hours on five planes in five countries, I got to Milwaukee International at two in the afternoon, caught up with my mom, and we drove home. We met up with friends and drank cider with brandy and played liar's dice.

Christmas morning, I woke up early to wrap gifts which were quickly unwrapped. I shaved my beard and my mom cut my hair. The family came over and we exchanged yet more gifts, and stayed up late singing and drinking.

Behold:

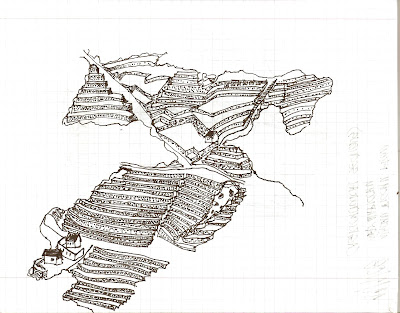

Wreckage on the Straits of Magellan in Punta Arenas

Friday, December 5, 2008

52 Pick-up

Thursday, December 4, 2008

Chiloé

Tuesday, November 25, 2008

Epilogue

After we got back to Cuzco, we booked tickets to Puno, starting our way back to Chile. By this time, Ezra and I were all that remained of our original foursome- a pickpocket and a family emergency split our other companions off to their own obligations. We decompressed on the tranquil, six hour ride- the same ride that took 24 hours in the other direction.

Part 4: Machu Picchu

In the morning we set off in a search for passage to Aguas Calientes, the tourist town at the base of Machu Picchu. Having only a few days, we ruled out hiking the Inca trail, which left us with the train. We booked tickets for the following morning and spent the rest of the day exploring Cuzco.

Credited as being the oldest continually inhabited city on the continent, Cuzco radiates a dignified antiquity. The cobblestone streets are asymmetrically laid out and lined with heavily-columned colonial buildings. Near the Plaza de Armas are a succession of town squares connected by narrow pedestrian alleyways. The Incan walls are composed of colossal stones which would inspire claustrophobia if you weren't so busy being awestruck. In an effort, perhaps, to outdo the Incans, the Spanish architecture in the city is similarly impressive. On the camino Santa Clara there remains a large gateway which frames the hills beyond it, and two large churches dominate the Plaza de Armas.

Cuzco's infastructure far surpasses those of the cities we passed through, maintaining a confident and sturdy atmosphere. However, it is abundantly clear that this atmosphere exists for the benefit of tourism. The influence of tourist dollars can be seen on every block, and it is difficult to find the honest and un-contrived Peruvian culture underneath. Still, the city is a remarkable destination. I met two nurses from Colorado who had been dispensing medicine on the Amazon. They shared their trail mix with me, remarking that Cuzco and Machu Picchu would be their recommendation to those having to choose a single destination in Peru.

The following day we rose too early for our hostel breakfast and purchased fruit and bread from Cuzco's central market. We wove through the throngs of travelers in the train station across the street and boarded with our provisions. The train rattled out of the station and crawled up the hills on switchbacks east of the city. Slowly, the track evened out into a gradual, winding path, and eventually straightened to an easterly heading. I struck up a conversation with a Dutch couple sitting across from me who were less enthusiastic about the early hour, and shared small bananas with a Japanese man in the next seat.

It took four hours to get to Aguas Calientes where hosteliers competed viciously for our business. We settled on a room costing one third that of ours in Cuzco, left our bags behind and sought out the bus to the ruins. A 20 minute trip up the mountainside left us at the entry gate to the city. I played the theme to "Indiana Jones" on my iPod as the ancient ruins came into view and my eyes teared up with excitement. We presented our passports at the gate, receiving this stamp:

On several plaques within the site North American professor Hiram Bingham is credited with discovering Machu Picchu, but many knew of its existence before him. It was Bingham's enthusiasm for Incan culture which brought about public knowledge of the ruins- his second expedition to the city was supported by the National Geographic Society. The ensuing fervor for the attraction has caused, some claim, catastrophic erosion on the mountain. On Waynapicchu, the peak just north of the large site, only 400 visitors are allowed per day to combat the gradual degradation. Rules are laid out at the entrance and appear strict and rigid. No food, no large backpacks, no smoking, no garbage. No walking sticks except for the elderly. Do not climb the walls nor write on the floor. Inside, sentries stand on peaks and scan the crowds, but can only blow whistles at infractions too distant to address.

A path to Intipunku, the sun gate, leads south-east away from the ruins and up a gradual slope. From the path's terminus the agricultural fields of Machu Picchu allign with the view and the site seems to stretch out toward Waynapicchu. From Waynapicchu the elements of the city are laid out as though a diagram, and visitors would stop and sit at length to dissect its intrigues and digest them to their satisfaction. The Incan empire, a flash in the pan, spanned a great deal of would become Peru, Northern Chile and Western Bolivia, but lasted only a hundred years. The function or purpose of the city remains under speculation.

We marched up and down the ruins for two days before returning to Cuzco filthy, aching and exhausted.

Photos courtesy of Ezra Riley

Monday, November 17, 2008

Part 3: Northward into Peru by Bus

"Cuzco or bust," I replied to the gringos, and they laughed at our casual ambitiousness. We had met two Estadounidense at the bus station in San Pedro de Atacama, Chile, northward bound like us. One read The Economist in the seat ahead, the other chatted with me about the Steinbeck book I´d brought. "It´s a shame I never read him in high school, I wish I´d paid more attention," I said, pondering the strange things you find yourself regretting. "Imagine what you´ll regret ten years from now," he replied, and I began calculating how much class I could stand to miss in the coming week.

"No, sit down, please; sit down!" Two days later, the Peruanas on the bus were desperately worried that the protesters would see us. Four white tourists onboard would not make a sympathetic case. Though we certainly wouldn't refer to ourselves as such, to the mob outside we were undeniably wealthier in material goods, and a direct affront to their cause. Days later we would reunite with a pair of European tourists, a woman with impossibly straight hair and a less memorable man who had been on the bus ahead of us that day- the bus which, unlike ours, had been allowed through the roadblock. The woman did all the talking: They achieved the feat by hiding under blankets while protesters examined the elderly and the weeping babies onboard. Had we only exercised such cunning discretion, ours might have been an equally short drive from Puno to Cuzco, one-time capital of the Incan empire.

In a happy accident, studying abroad in Chile for the "American" fall semester means you effectively get two spring breaks in one year. Three of my fellow students and I took advantage of our week off to have a go at Machu Picchu, the lost city of the Incas. Already in San Pedro, a desert oasis half-way between our Santiago school and the northern border of Peru, we could think of no more opportune time. We boarded a series of buses ferrying us to Arica in the North, where a taxi hauled us through customs and up into Tacna, where the Beach Boys' "I Get Around" played on the radio. We exchanged pesos for soles and began inquiring with bus companies how to get to Cuzco, the oldest continually inhabited city in South America and staging area for all visitors to Machu Picchu.

"No es possible," was the reply. Ezra, the closest thing we had to an interpreter, could get no more information than this: roadblocks in Moquegua were blocking all traffic north. Either Ezra´s Spanish was faulty, or, what seems more likely, the company representative was unwilling to say. So the nature of these roadblocks, be they natural or man-made, civilian or government-imposed, went unrevealed. A man approached us as we milled disenchantedly through the bustling terminal, and with a smile of rotten peanuts where his teeth should have been, he said hopefully, "Arequipa…?"

In a national park there, "andean condors regularly swoop low above pedestrians´ heads," reads the Arequipa section of Lonely Planet´s South America on a Shoestring. The price was right and the bus was leaving shortly. Peanut-Teeth arranged our tickets and departure tax and hurried us on to the clean, professional-looking double decker coach for a meager tip of one sol (about 33 cents, U.S.), and we set off northward. Sure enough, on a bridge in Moquegua, a battalion of riot-gear-clad police stood in a phalanx, swiftly separating to let us pass. Whether this was a government roadblock or a government's response to a civilian roadblock we could not tell, but we went on to Arequipa without another sign of trouble.

From Arequipa to Puno the scenery changed drastically. Jagged and unaccommodating Peruvian desert gave way to rolling, yellow-brown hills. More and more frequently, our driver would honk at vicuñas in and beside the road. Into Puno's Terminal Terrestrial after dark, we heard a familiar report. several companies announced with nonchalance that service to Cuzco was interrupted indefinitely. Our spirits fell with the news, and our nerves frayed under the oppressively shrill calls from ticketers hawking the final seats on their coaches, "ArequipaarequipaarequipaarequipaaaaaAHHH!"

It was here we first met the European woman with impossibly straight hair and her unimpressive counterpart. They were carrying their bags with a determination which inclined us to ask where they were headed; "Cuzco" was their reply. We followed them to a ticket counter in a far corner of the terminal which would have done little to inspire confidence but for the crowd of patrons assembled nearby.

Peruanos, it would seem, employ bus travel for all means of cargo transport, and it is not uncommon to witness large sacks of seed or produce being dollied, hauled, or otherwise dragged into stowage compartments under the coaches. There was a memorable instance where I witnessed a small, splintery, wire-bound wooden crate containing an indeterminable but very alive creature on a woman's luggage in a terminal. In Puno that night, humans comprised the only live cargo our bus would haul, but the sacks and blanket-wrapped parcels in piles by the counter gave the very real impression that our foursome could be in Cuzco by the following morning.

"She says it'll take twelve hours instead of six," Ezra reported. We conferred, agreeing that to depart immediately on a 12-hour bus seemed more prudent than waiting indefinitely for a six-hour trip. The bus departed not from the terminal, but from a low-lit side street a block away. The night had grown drizzly and obscure. We were the only gringos among seats of Peruanos, mostly heavyset, blanket-clad women, faces creased with endurance. With a shudder, the aged and fraying coach rumbled off indeterminably; northward, we could only hope.

I awoke chilled by a draft coming through the window and rose to gather extra shirts and coats from my bag. The bus stopped at the side of the road and we debarked to relieve ourselves. Women walked a few feet off the pavement to hold their skirts up in bunches. Setting off again, we slept until dawn, when the coach stopped abruptly in a small village. There was a buzz of rumor.

Debarking, we met the straight haired European coming from the bus ahead. She expressed offense at the piles of rocks in the road impeding our travel. "The government wants to build a hydroelectric dam, and the people don't want it because it will stop their water," she explained with distress. Villagers wrote their politics on the windows of our buses with chalk and soap. "I don't know what they're doing. What does this have to do with us?" she said, furrowing her brow. A man from our bus who the other travelers referred to as "Professor" discussed the situation with men from the village. He returned with a leafelet and we were allowed to pass.

We encountered another roadblock near Laguna Pomacanchi at noon. Flamingos stood on their heads in the shallows nearby coaxing brine shrimp from the sand, and crowds of chanting villagers filled the narrow street, rolling enormous boulders onto the asphalt. It was here I stood to better view the situation outside, distressing the other passengers. Our Professor had abandoned us for the bus which had been allowed through, and our remaining negotiators surrendered to the impermeable fervor of the mob. We reversed the length of the waterfront.

South of the laguna, we turned onto a road which led up a mountain on the Western edge of the water. Again we encountered boulders in the road, these having originated in a rockslide. The four of us and a young Dane helped workers clear the obstructions. Beyond the rocks, villagers were clearing the mountainside below of firewood, and had been stacking their bounty on the road all morning. We continued to march ahead, pushing felled trunks and split wood as close to the mountainside as possible, while the bus puttered behind, sometimes with less than ten inches between the edge of the road. Some of the tree cutters aided us, some continued their work, and one held out his hat for soles. Beyond the mountain the road was paved and level. We passed through a few small towns, clearing away piles of smaller rocks presumably left behind by the protesters converged at Pomacanchi. One barricade consisted of logs bundled together with wire, which I helped our navigator displace. After the bus passed through, she waved me over to return it to its original condition.

Further north, we reentered the perilous Andean roads, our driver deftly engaging the switchbacks, climbs and descents. Our speed never exceeded 25 miles per hour; no faster would the rough-hewn dirt road allow. On two occasions did we meet vehicles coming from the other direction. One was a dump truck far too wide to pass us, and we had to reverse a quarter of a mile to allow it to pass. The other was an ambulance which took fifteen minutes to navigate the outside edge of the road around us. The children of the mountainside towns we passed through would run alongside the bus, smiling and shouting, and occasionally wearing a look of bewilderment. More than once did the passengers debark to cross, single file, a bridge of questionable integrity. The bus would then line up with the structure and shoot across in a burst of speed. Darkness fell as we passed through Rondocán, and it was near midnight when we emerged from the mountains into Cuzco.